Source: Reuters

Imagine the world uncluttered with physical objects. Imagine the world in which your space is defined by what is not there, rather than what is. Imagine the world in which our homes contain only what we need. What we really need, and nothing more. In Japan, they call it Saishogen-Shugi, a deceptively exotic sounding phrase that blandly translates as “Minimalism”. In practice, this refers to an extreme brand of urban asceticism that shuns the material excesses of our age, stripping back our lifestyle to the barest essentials.

Zen and the Art of Living

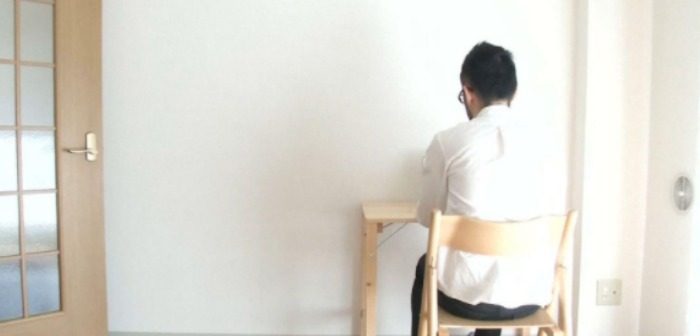

I visited the home of Fumio Sasaki on a recent trip to Tokyo. From outside it looks like any other Japanese apartment. Once inside, the pulsating energy of Tokyo was replaced with a feeling of serene calm and beauty, at once empty yet full of unspoken potential. This was truly minimalist living. One tiny table, one chair. One cup, fork, knife, spoon. One set of chopsticks. The single-room dwelling was so sparse and immaculately clean that you could be forgiven for thinking that he had moved in that morning and was waiting for the van to arrive with his belongings. However, Fumio has been living here for over three years in serene, blissful simplicity.

It is unsurprising that Japan has become the de-facto home of the minimalist movement. The birthplace of Zen Buddhism, which eschews the trappings of the material world for a more enlightened, spiritual existence is still a strong, albeit unconscious undercurrent in the Japanese psyche.

Keeping Up With the Tanakas

I chatted with Fumio for a couple of hours, trying to understand his motivations and ethos. Not long ago, he was just like most of us: going about his everyday life, steadily accumulating stuff that began cluttering his environment. He explained how he would occasionally sort through his belonging, discarding items that he did not need or use. On one occasion, he began to ponder taking things one step further. He realized that his unthinking acquisition of material goods was motivated more by an insecure need to keep up with latest trends and impress his peers than fulfilling his own internal needs. The deliciously cathartic experience of ridding his life of extraneous possessions highlighted that on a spiritual level he was craving simplicity and serenity, rather than more books, CDs and trinkets.

In days gone by, Fumio may have escaped to a mountain somewhere to live the life of a Buddhist monk. For a young, attractive, professional man in a modern world, there had to be a more practical answer. Fumio thus began building his own island of calm in one of the most hectic places on a hectic planet. Aside from the obvious changes in lifestyle, adherents point to other benefits of their lifestyle choice. Less expenditure on unnecessary items means more for leisure, travel, savings or investment. Many report significant psychological and cognitive advantages. Fumio spoke glowingly of how the lack of objects in his space has led him to populate it with his imagination. This has led to a marked increase in creativity in his professional life as an editor and his passions for photography and creative writing. Furthermore, he says that radically reducing the number of belongings causes one to think very carefully about the purpose of each and every item. This, in turn, engenders an enhanced sense of appreciation and gratitude that permeates his attitude to other people and life in general.

Living Minimalist for Dummies

Even the most devoted minimalist understand that these extremes are not for everyone. This does not mean that the rest of us can’t implement certain aspects to improve our lives. As Fumio put it so succinctly; “every inch of space cleared of materialism creates an equivalent amount of space for your mind to fill with imagination, dreams and introspection. It doesn’t have to be all or nothing.”

What a beautiful article! Really thought provoking. I’ve been thinking about decluttering my life for some time and would be interested to hear if any other readers have had similar experiences?